What it’s like for real people

Rereading New Statesmen Epilogue and Prologue by John Smith, Sean Phillips and Jim Baikie.

There was a time, about 10 or 12 years ago, when the DC universe was dominated by a new generation of its marquee heroes. Grant Morrison’s JLA had Wally West, Kyle Rayner, Connor Hawke, Steel, Zauriel who was intended to be a new Hawkman, all younger replacements for the guys who’d been around since the Silver Age. The comic had real sparkle because of it, exploring the interactions between these Gen-X guys who’d ended up wearing the tights one way or another, for who saving the world alongside Superman was still new. But even before the New 52, the clocks got turned back. All the old guys came back and the new guys got demoted to backups, given new names, made superfluous. Big Two comics, perhaps because they’re a business based on intellectual property that nobody’s creating anymore, aren’t good with change.

Creators in the Dark Age, on the other hand, liked to kill superheroes. It was one of their marked differences from their predecessors. And there were too many New Statesmen anyway, so it’s hardly surprising that John Smith felt he could off a few. But he didn’t do it the accepted way; sure, Burbank got killed in battle. But the next two Statesmen to die, in the epilogue, died unheroic deaths. How else would they die? They don’t have villains to kill them in battle. None of the three British superheroes I’ve written about so far had villains to fight: a Nazi relic, a big green dog, that’s all. Their villains were their heroes. The Marvelman Family and Cloud 9 turned on each other. Two Statesmen are dead and one is a semi-sentient wet spot by the epilogue, and if we hypothesize that Mitchell killed Burlington then all three died at the hands of their fellow Statesmen. And we are close to more endings.

The first half of the epilogue is all about Cleve. The retirement we saw him enjoying is on short time. He’s been told he’s going to die. What nobody knows is how. He escapes an easy death in captivity for the wilds of the United States, his final odyssey taking the classically American form of a roadtrip. But this isn’t an exploration of territory or a journey of discovery. It’s a terrified flight from something unnamable and unknowable, a death which rises from inside and literally taunts the dying.

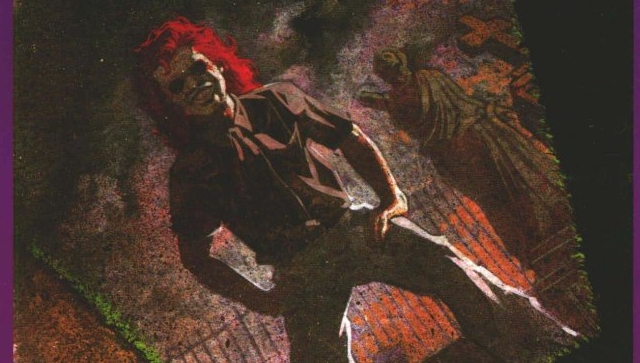

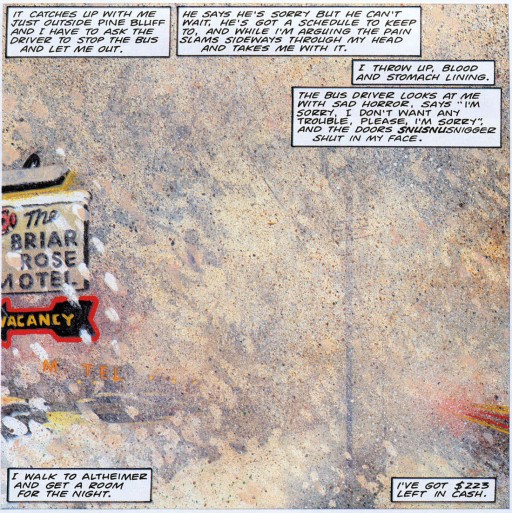

The sense of despair in these 15 pages is oppressive. Every page is packed with panels and every panel is packed with captions, the image of Cleve missing from Blanchard’s monitors sharpening on our own, going into granular detail as his body falters and fails. The landscape is whited over, details obliterated, reduced to a motel, a truckstop, a gun shop. The page in which he’s thrown off a Greyhound and abandoned, vomiting blood at the roadside, shows none of what we’re told happens. Only a motel sign’s neon is visible through the static of the snow. Cleve treks through the drifts of abandoned cars to meet the Angelus, the dark-socketed shock-haired creature that appears to be the ghost of the Statesmen while they’re still alive, shirtsleeve-clad in the cold. Even then he’s halfway between hallucination and real. His mockery gets no response from Cleve. Has he even seen him? Does he have to pretend he hasn’t to keep going?

After a murder and a failed suicide attempt – still invulnerable enough to be forced to live – the trek moves from desperate to desperately futile. The animal instinct driving Cleve turns out to be nothing but animal. He breaks his arm, he collapses on the ice, he dies lost and unknown. A superhuman becomes a human, becomes mortal, becomes dead. It’s a haunting, high-velocity decline, straightforward and chilling in execution.

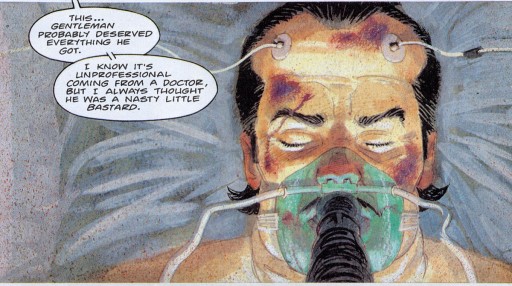

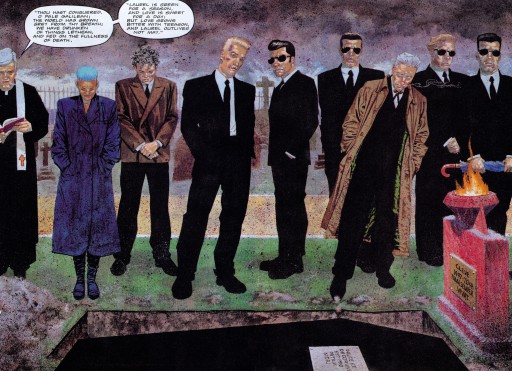

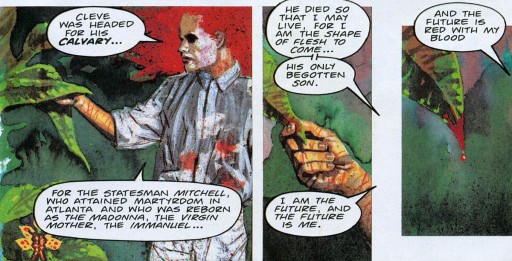

After that comes the funeral, and our last chance to see the Halcyons. They’ve not survived the series well; Vegas is in hospital, and the other three are struggling to recover from their toxic and near-fatal love triangle. Meridian, after a skin-crawling dream starring Statesman Mitchell, meets the Angelus. Who is he? What does Karikura mean? Even Google doesn’t know the latter, and perhaps only Smith knows the former. All we know is what we’re told; he is an entity that is part of the Statesmen and who becomes stronger, more complete, as they die. He appears in Cleve’s dream and his death hike and at the wake. But his objective reality is never established. He could be a vision or physical, real. This far post-human, the difference is eradicated. Whatever he is, he’s disturbing. A clown sent as a harbinger of the apocalypse, a cheerful visitor from the sunless lands, a presence for who death and disaster are the baseline state. And he’s getting stronger. Vegas probably dies immediately after the epilogue, suffocated by a League of Light believer. And few of the rest survive the next 16 years.

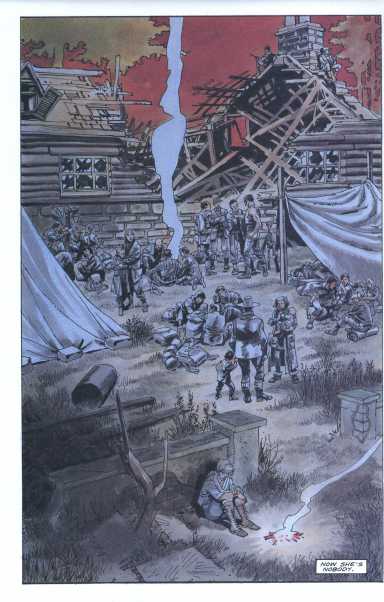

Sean Phillips handles the art for the epilogue in what at the time was his signature style: painting over pencils, lots of airbrush spatter everywhere. It’s wonderful work. The occasional lack of polish, the inexperience that shows through, is nothing compared to the freshness of it, the neophyte’s commitment to the wetwork of comics. John Smith has a signature way of using splash pages. He doesn’t use them for moments, for punches or big reveals. He uses them as punctuation, as ways of laying the mood of a scene starkly bare. Baikie does this nicely in the prologue, the full page of the survivor’s camp with LeJeune isolated at the bottom, but it doesn’t compare to the two-page scene at Cleve’s graveside where Phillips poses suits of perfect black against a lurid backdrop, the death already almost a joke to anyone that matters.

John Smith employs next to no postmodern trickery in his final three chapters of New Statesmen. The first part of the epilogue is entirely first-person; Phillips interpolates maps and notes but it’s almost all from Cleve’s perspective and every caption is his. The following funeral chapter does almost everything, including an encounter with a being in an indeterminate state of reality, with dialogue. And the prologue begins with third-person first-person captions, inside LeJeune’s head but without the I, though the bulk of it is that old device of illustrated exposition. One character telling another what they both already know.

John Smith employs next to no postmodern trickery in his final three chapters of New Statesmen. The first part of the epilogue is entirely first-person; Phillips interpolates maps and notes but it’s almost all from Cleve’s perspective and every caption is his. The following funeral chapter does almost everything, including an encounter with a being in an indeterminate state of reality, with dialogue. And the prologue begins with third-person first-person captions, inside LeJeune’s head but without the I, though the bulk of it is that old device of illustrated exposition. One character telling another what they both already know.

It might seem perverse to cover the prologue last, after the epilogues, but they’re really all of a piece. The prologue was the last part of the series to be published, six months after the epilogue in Crisis #28, and very probably the last to be written and drawn. It was created for the trade paperback and bear clear editorial fingerprints: explain the world a bit more, John and Jim. Help the readers. Stop them from being turned off by their own perplexity. So LeJeune, the former pin-up Statesman from Florida seen on TV in the first chapter, takes us through the history of her world from terrorism in the EEC to a South Africa that keeps apartheid going for fifty years. Apart from a couple of arresting images, like a baby Statesman attached by umbilical cord to a whale, it doesn’t add much to the whole and certainly doesn’t clarify anything. You can’t mitigate the effects of a narrative founded on disorientation by preceding it with old-fashioned storytelling that only misses LeJeune’s floating head talking us through the years.

Especially when the prologue is itself wrapped in a framing sequence, set the aforementioned 17 years after the main story, that provides the reader with an entirely new scenario and a bunch of indigestible information hinting at yet more key events we’ve never seen. We are post-apocalypse, painted by Baikie in unrelenting browns and blues. The apocalypse was related to the Mark III Optimen, the Statesmen’s successors with even more Soft Option psychic talents, and to the Spur kicking in, which depowered the rebellious Statesmen, used ley-lines to conduct power, blew shit up and welded people to buildings. Like Atlanta and Burlington writ large, which would be helpful if we knew what happened to Burlington in Atlanta. Whatever happened, all but nine of the Statesmen are apparently dead. Some are in Scotland. And Wyatt, the homoerotic Arnold Schwarzenegger fantasist in leather dungarees, is the vessel charged with the power of the Angelus and the hope of the survivors. Everyone – human and superhuman – is fleeing America, camping in ruins, washing in rivers, hiding in shadows.

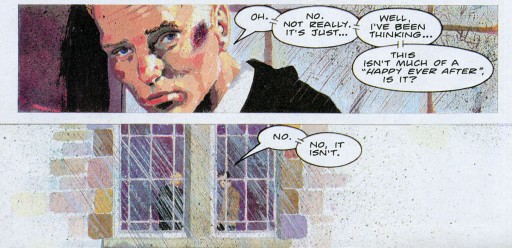

The Dark Age was, as its name suggests, characterized by comics that took superheroes into a twilight realm of grubby morality and extreme violence. New Statesmen is no different. It is both grim and gritty. But it’s reaching toward something else. The three British superhero comics, in their own way, each consider humanity and super-humanity. Gaiman’s Miracleman run is about the human failure to understand heaven, to accept boundless happiness. Zenith is about how humanly superhumans would behave, about great power fuelling irresponsibility. And New Statesmen was heading towards a consideration of how a human would feel in a world of superhumans; how it feels to be inferior, to not be evolution’s pinnacle, to be replaced.

Was the prologue set after the events of any possible second volume? Would the second volume have gone straight onto the 3G Optimen? Would it have starred the Halcyons? We’ll never know. John Smith takes his time writing, but after 24 years I think we can safely say this is abandoned. (When I spotted an error in the first half of the epilogue – Cleve mentions Bremerton as a dead Statesman rather than Burlington, when according to Crisis #7’s roll-call Bremerton is very much alive and running a school of archaeology and ethnology – I realized that in the last few weeks I have very likely become the world’s foremost expert on the New Statesmen.) If I imagine a second volume, it probably stars Statesmen we met briefly if at all. It’d be set a few years after Phoenix but before the Spur. It might explain Atlanta and the significance of Mitchell. And it wouldn’t be as clever, as tricksy in technique, as the first volume because Smith and Baikie and/or Phillips would be more confident about the story they wanted to tell. They wanted to write about genetics, and cancers, and the news from our genes that we are foredoomed even in the manner of our doom. They wanted to use super-humanity to examine humanity, to teach us about our mortality by showing that even our power-dreams are mortal, and to consider a world where death is not a possible consequence of losing a battle but the inevitable consequence of being alive.

Because we’re all the new batch of Optimen when we first come along, aren’t we? Better than the last generation, more technologically advanced, looking down on them with talent and good looks to burn. We’re all the hot new thing seizing the day which is rightfully ours. And we all, in the end, get replaced.

New Statesmen Epilogue and Prologue by John Smith, Sean Phillips and Jim Baikie appeared in Crisis #13-#14 and #28, in New Statesmen #1 and #5 and in The Complete New Statesmen trade paperback, all of which are out of print.

Comments

8 Responses to “What it’s like for real people”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...-

[…] about New Statesmen in an early series of blogs about British superheroes, spending three different blogs proving, at least, that it’s somebody’s favourite. I’ve written about the work of […]

Found your site while trying to find out if anybody has said anything on the internet about ‘Mr Soft’, the excerpts from a made-up-novel which is included as supplementary material toward the end of The New Statesmen. I’m working on a series of portraits of the character, running with my own style from the Brendan McCarthy original as well as using elements from the presented story, and wondered if anybody else had attempted it: as far as Google is aware, I’m the first.

I’m very late to The New Statesmen — I was reading 2000AD when it was running in Crisis, but I was 11 at the time so my only memories of the original run are of it on the newsagent’s shelf. Then I took the customary break from comics during my late teens/early twenties so that I could spend money on drink and tobacco, and in the past two years have been working my way back in, partly through my own efforts to produce comics.

Even in early teenhood, when I had no real idea of what he was doing, I was a fan of John Smith’s, and it’s his work more than anybody else’s that I’ve been revisiting, and through that process came to The New Statesmen a few months ago. I realised soon after beginning it that to stand any chance of comprehending what was going on I was going to have to steam through a first read and then revisit it afterwards, putting clues together on a second or third reading to really get my head around it.

In this respect, the closest comparison I can draw to it is the work of Thomas Pynchon, especially Gravity’s Rainbow or V, where the reader is bombarded with information, some of it pertinent, some of it not, some of it correct, some of it only correct if you take into account a particular character’s bias and some of it wholly unnecessary.

Without a copy of the collected edition to hand, it’s going to be hard for me to elaborate on any other points I’d want to make, so I’ll leave it there. Especially since I’d only started writing to thank you for taking the time to write about this series, which I’m a passionate advocate of, in such detail and with such clarity.

I’m off now, but I’ll be back to read your other articles soon.

Thanks for your kindness, sometimes it can feel like nobody else cares about something as obscure as New Statesmen when you’ve spent close to a month writing about it. Agree with your Pynchon comparison; there’s a particular gleeful joy in a writer who decides they’re throwing in everything they want to, even if not all of it really fits, and it’s something we’ve not seen enough of in comics. Huge amounts of what Smith includes has no narrative payoff – Mr Soft is a prime example – but almost everything has some tangential relationship to the whole.

I’m presuming you have the collected edition of New Statesmen, with the extra pages of Mr Soft? Your portraits sound like an interesting project. Smith is fairly accessible, I believe; I’ve interacted with him, via a mailing list, many years ago and I don’t think it would be too difficult to find him and tell him about what you’re doing. I’m sure he’d be glad to know that a piece of work that he believed in is still having an impact.

Hi again,

Just to answer a few points: Yes, I’ve got the collected edition — I hadn’t realised that there was ‘extra’ content in there, though… I’ve finished the four images I set out to do, and once they’re published I’ll share them publicly, but since you’re one of the only people I know of who has any idea what I’m talking about when I mention the project, you’re welcome to have an early look. I’ve sent John Smith the same offer via his 2000AD Forum account, so we’ll see how that goes.

My memory once again proved unreliable – the only Mr Soft content that appeared in Crisis was the full-page image by Brendan McCarthy reprinted in the collection, and all the text was new to the collection. Look forward to seeing the images when they’re done…

Hello again,

Have just read New Statesmen again, and came back to revisit your articles as they’re essentially the only point of conversation I can have about the book. Despite its flaws, it’s still one of my favourite comics. There’s a quote somewhere by Jim Jarmusch that I’ll have to murder through paraphrasing: “Never answer a simple question directly” or something like that. And it’s fiction that applies that rule that I’m drawn to — David Lynch, Jarmusch, Pynchon, that breed of creator. And it’s for that reason that I keep returning to the Statesmen, because there’s just SO much that’s unresolved. We don’t meet all of the Statesmen, and other than Phoenix, Blanche and the Halcyons we really don’t spend more than a few panels with them. There’s a whole 17 years between the prologue and the main story (and Jesus, is that prologue perverse in it’s total rejection of what a prologue should be for…) I’m still not entirely sure who the Tamarisk are.

It’s those things that keep me coming back to it, as well as the energetic art. It feels like it was made by desperately ambitious people, and I admire that entirely. To compare it to music, I always prefer a band’s first couple of recordings to whatever they record after they’ve worked out how acheive the sound they’re aiming for/learn how to play their instruments.

As for the illustrations I was doing of Mr Soft — they got finished, although the zine fell through. I was really happy with the process I took to making them, which is enough for me. Here they are: http://abstractcomics.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/mr-soft.html

I’ve just finished another page of my own comic which directly lifts its panel positions from one of Sen Phillip’s pages from the Cleve epilogue, and that’s here, again if you’re interested: http://abstractcomics.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/the-intercorstal-new-statesmen.html

Fantastic art. I own that Abstract Comics book – is your stuff in it? – but found it generally disappointing because the artists didn’t appear to have a deep understanding of comics. They’d lay down a nine-panel grid and imagine they were innovating by showing time passing incrementally, with no knowledge of how much comics has already done with the grid in terms of shifting perspectives, lines of action, storytelling, whole page designs, etc. But non-comics people thinking they’re bringing something wonderful and fresh to the medium without researching it are a pet hate, just as non-sci-fi writers create a dystopian future without realising the same one was done 40 years before.

There isn’t enough confusion and ambition in comics, you’re right. We’ve mentioned Pynchon but Infinite Jest is the comparison I come back to with New Statesmen; you’re left to work out so much for yourself, to put major incidents together from the oblique glimpses, and nobody does that anymore. Even in alternative comics everything’s done pretty straight. There are good reasons for that, chiefly commercial; if your Image comic confuses and baffles readers, they’ll probably drop it. And between appealing to the conservative readers of the direct market mainstream and the bookstore readers who approach comics with a certain trepidation anyway, it might kill your career to take chances. But it means there’s a level of sophistication, where questions are being asked of the reader, that we just don’t reach. Not that New Statesmen was always there – the big fight with Phoenix is straight Kirby – but it tried.

BTW, pretty sure the comment by Johnny Mondo on my first New Statesmen piece is from John Smith himself. I emailed him, including a link to your Mr Soft project, to ask if he could answer a few questions about New Statesmen and where Book II might have gone. He didn’t reply.

This is a pretty late reply, considering how long ago you wrote this piece, but having just come across it (while, ironically, trying to search details of the trade paperback for New Statesmen) I had to just tell you how glad I am to find someone else who so enjoyed the world created by Smith and Baikie. I began as a 2000AD collector, before moving onto Crisis when it came out (I was in my late teens, so it perfectly appealed to my political sensibilities of the time).

However, it was Third World War that gripped my attention, with New Statesmen being too confusing and random for me – it also didn’t help that growing up in overtly Calvinistic religious South Africa (which was also in the dying days of Apartheid) I was horrified by the fact that some key characters like Dalton and Burgess were gay (or bi-sexual). However, I have kept returning to this confusing world time and again, getting more and more from it every time (I like to think I know what happened in Atlanta, although of course that’s just my own view in my own head as to what occurred, but it isn’t often a story built on pictures leaves you with room to create parts of it in your own imagination).

I consider New Statesmen to be one of the finest (if not THE finest) of the limited series produced by British comics in the 80s and 90s – the only one that can compete for me is Miracleman, although I sadly never got to read the end of that one. (although kudos to Grant Morrison for his Zenith series, which is also high on my list of favourites) I also like to think that the portrayals of Dalton and Burgess – and the love triangle with Meridian – helped at least a little in humanising gay/bi people and making me realise that the things we were being taught and indoctrinated with here in SA at the time were wrong. I have no doubt that Crisis in general and New Statesmen in particular played a role in defining my changing attitudes to politics, religion and sexuality, and I have yet to see another comic portray gay people as simply human – rather than being some kind of camp or butch caricature.

Anyway, still got lots of work to do and I want to give the series another read tonight. Thanks to your article I now know something I didn’t before – that the final chapter released in Crisis 28 was actually the PROLOGUE. I’m going to have to read it with that in mind and then see how that impacts my understanding of the story.

Thanks for the interesting article and for reading the ramblings of a huge New Statesmen fan, 25 years down the line!