Going nowhere, connecting with nothing

Rereading Bible John: A Forensic Meditation by Grant Morrison and Daniel Vallely.

Being honest: I never believed there was an actual living rivalry between Alan Moore and Grant Morrison before the latter’s freakout at the end of last year. I mean people have always talked about it, or they have since comics fans found each other when the Internet fired into life, but I’d never seen proof. And when Páidraig Ó’Méalóid collected all the slights together for The Beat last year, it still wasn’t especially convincing. A snide swipe in a Speakeasy gossip column, a couple of offhand remarks in interviews. There wasn’t the evidence for a magewar, until Morrison weighed in with a lengthy and self-contradictory rebuttal that was the wonder of the comics world until something else came along.

The feud proved to be real on one side at least, then. But the accusations of plagiarism – no matter who copied who – still seem to be unreal. The two writers have certainly explored similar areas. Both are practicing magicians fascinated by Alastair Crowley. Both are interested in the self-awareness of fiction, in fictions that know their condition and how that relates to our supposed reality. Both have proved to be fonder of superheroes than their peers, returning to the closed system of icons and values and using it to articulate larger ideas. And both, in the creative freedom of the Dark Age, decided to use the comics form to explore the circumstances of, and the world surrounding, a notorious and unresolved murder.

Alan indisputably got there first. Although Bible John was published in early 1991 and the first issue of From Hell didn’t come out until late 1991, it began within Steve Bissette’s Taboo anthology in 1989. The crime was the same but the history was very different, Jack the Ripper being almost mythology compared to the relatively recent history of Bible John, and the approach was very different. Moore and Campbell for the most part play their narrative straight, a chronological recounting of events told directly through their depiction and dialogue, while Bible John is entirely abstract. But the two works do have one, overarching similarity; the unmistakable influence of the writing of Iain Sinclair.

If you’re going to be influenced by anyone, then the extraordinary and unique Sinclair is a dubious choice. On the one hand his work explores areas unlike anyone else’s, weaving memoir and place and history and learning and perception into a single cloth, indivisible and whole. On the other hand, nobody else can do what Sinclair does. Nobody’s really come close to that prose; dense, allusive, serpentine and shimmering as the river that winds through his city and his books. You read Iain Sinclair by plunging in, stroking through the images and links and namedropping and the connections between low and high culture, between the man on the street and the man in the surveillance hub and the man writing mad-eyed tracks in a tower on the Welsh border 150 years ago or today. It requires a huge amount of trust from the reader that all these random siftings of information will among to something, that the hard work will pay off. Sometimes it doesn’t, and I gave up on Edge of the Orison before the bit where Alan Moore joins him for a walk (and Mancunian landscape comic creator Oliver East has also walked with Sinclair), but when it works it’s spectacular. The end of Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire, which I’d struggled through, justified every word and moment spent on the aged left-wingers who populated it. It was dazzling.

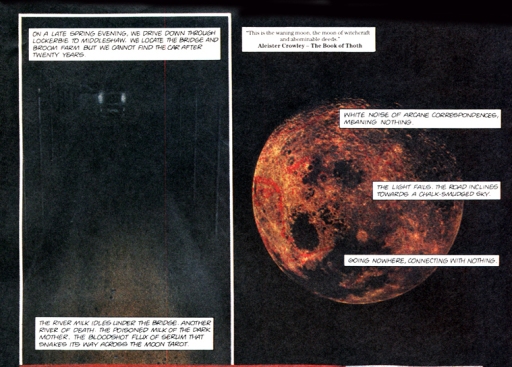

Sinclair’s influence on From Hell is on content: Lud Heat, his poem, and the novel White Chappell Scarlet Tracings were both chiefly about the Ripper murders and the psychogeography of the landscape around them, invoking Gull and Lees and the Knight theory. Useful information for your next rampage through a comments section, Moore-is-a-plagiarist trolls. The Sinclair influence on Bible John is on form, the angle of attack: taking a notorious murder case and examining it through exploration of the murder sites, the symbolism, the linking of serial murder and magical ritual, the charged atmosphere in which there are no coincidences, the prophetic dreams, the elegiac failure of the whole enterprise. And while Morrison isn’t the prose writer Sinclair is – few are – he can float poetic lines onto the page in captions, and of course he’s got that whole other thing. The pictures.

Multimedia was a thing back then, a buzzword. Painted comics were one level up, fully painted comics ie no ink were up again, and at the top of the pyramid was multimedia. Meaning anything and everything, three-foot high pages with circuitboards on like Dave McKean did for Arkham Asylum, pages with patterns and fabrics like Bill Sienkiewicz was doing all over the place. Throwing everything at the page, trampling barriers just to see them broken down. Daniel Vallely’s art on Bible John is a fine example of a vanished movement.

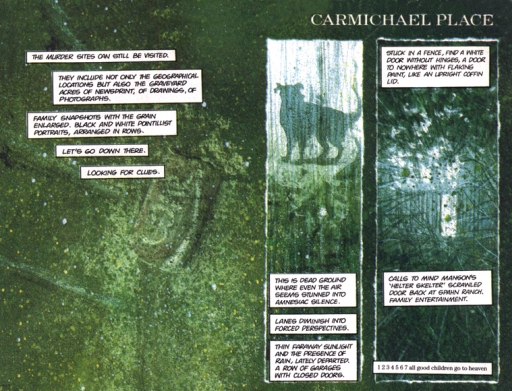

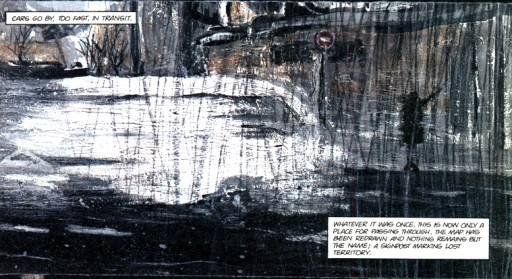

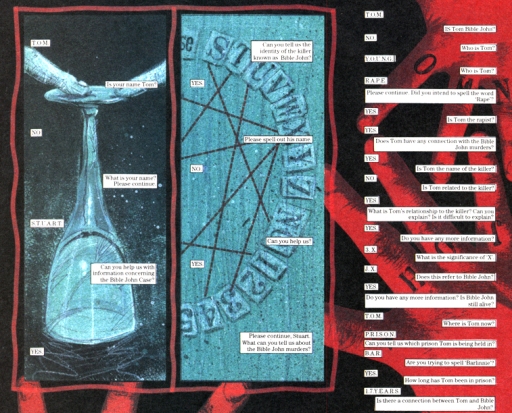

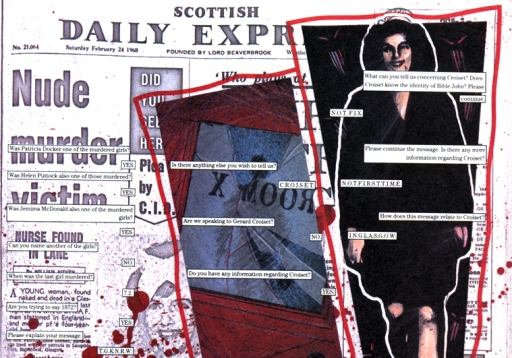

The first page is a filtered photograph. The second is a collage, painting and sculpture and object and sampled images making a multimedia demon. Then there’s a page that’s mostly pencils with spot colour, and it’s only on the following page we get to the scratch-and-spatter paintings that form the spine of the narrative, that we revert to whenever Vallely isn’t trying something new. It’s a pragmatic approach to producing a comic like this, abstract, strange and visually arresting; you can’t be all fireworks all the time. Telling a story, even as fractured and non-linear as this, requires intervals. Nevertheless it’s rare a few pages go by without some new visual texture changing the tone, demanding the reader’s attention: stitched-together maps, monochrome glitz, primitivist paintings, roadkill puppets, newspapers so blown-up they’re nothing but grain. Grant’s captions provide a thread that the artist seems free to illustrate or deviate from, full-pages asking the audience to make sense of the juxtapositions.

The subtitle, A Forensic Meditation, sounds a bit hazy. Actually, though, it’s trying to give an accurate impression of the shape of the thing: this is not a story. Or an essay, or a memoir, or even a poem. It’s the illustration of a process, an investigation into real events that contains no fabulation, no fiction, that is all fact apart from the subjective viewpoint it comes from, the absorption of evidence from areas not considered by the murder police. Maybe that would’ve caused trouble if Morrison and Vallely had come up with a solution, pinned the crimes on a name, but solving the crime isn’t quite the point. It’s the evidence, the approach. Murder causes psychic disturbances in the strictest definition of that word. It causes people to think differently about people, physical locations, their own safety, the safety of their children. It resonates. I’ve studied and worked in places that are only known because of murderers, and when Morrison mentions Lockerbie in this comic the mind immediately flashes on what happened there, the number of lives ended. So there’s a backwards kind of sense in approaching a murderer, a series of crimes that consumed a community, through the psychic hole it left in the landscape.

The first couple of chapters are the evidence. Visits to the murder sites by the artist and writer, never depicted, narrated in captions and snippets of quote from other sources. An account of the crimes and their locations, a triangle drawn on a map. Newspaper cuttings, descriptions, a likeness done at the time, the murder weapon. Outlining what’s known. Chapter three concludes the scant detail and looks, with the following chapter, at the lines of investigation followed, the patterns searched for, the involvement of medium Gerard Croiset, the reconstructions and wanted posters and The Marine Police Formation Dancing Team, undercover police at Glasgow’s Barrowlands where the victims met their murderer. It follows the trails that turn cold, Morrison throwing in a few possible leads of his own like the Thuggee cult and the bloody flavour of the times. And the fifth chapter, the penultimate one, is the heart of the matter. The first half is seance, asking the uninterviewed witnesses to take the stand. Asking the dead about murders. It produces odd results, clues askew, details around the murder but not necessarily germane to it. And it’s fascinating reading, an account that there seems no reason to doubt. The second half of the chapter, cutting up the text that’s been presented already to create new juxtapositions, new insights – basically what Crazy Jane does in an early Grant Doom Patrol – doesn’t have the same unearthly grip but keeps us afloat in this strange atmosphere of spirits and portents and omens. And the final chapter brings us back down to the ground, bandmates Morrison and Vallely following up their leads in the library and in the terrain of new towns and farmland surrounding Glasgow, looking for a clue and finding nothing they can use, stalling at the limits of their bravery and powers. It ends up nothing.

Bible John the comic isn’t nothing, though. I remembered it as one of the slighter stories Crisis had to offer, a bold experiment but an artistic dead end. On rereading it’s still a dead end, an attempt at a new direction never followed up, but it’s a surprisingly complete piece. It lives on the page, lives and breathes, the artwork slightly dated but the abstraction still narrative, still storytelling which many abstract comics fail to be.

Bible John by Grant Morrison and Daniel Vallely was published in Crisis #56-#61 and has never been reprinted. I’m making it available for download here.

Thanks very much for making the strip available digitally. Your reference to comic readers finding each other via the internet is apposite, since discovering your writing on Crisis is like finding a diary detailing the experiences and opinions of my teenage self. I wasn’t sure anyone else remembered or cared about this stuff.

It’s also relevant because I’m not sure I had ever teased out the details of whether Moore or Morrison was first into print with their serial killer investigations until the advent of the internet war between the two.

I didn’t start reading From Hell until its second or third appearance as a solo title, and the odd telescoping of time during a period of radical physical and mental development means that the memories of the schoolboy who read Bible John in a comic he had on order from his local newsagent and the apprentice who picked up issues of From Hell out of sequence on his travels around the country seem like they belong to different different people and happened decades apart.

Thanks for the article. I hadn’t paid much attention to Bible John at the time (too young) but have revisited it since.

Fantastic writing on this review. Bravo.