Never let memory step on your shadow

Rereading Hellblazer #31 and #34-#36 by Jamie Delano and Sean Phillips.

Where does the story arc come from? From which comics did it arise, and how did arcs become the standard unit of comics storytelling?

In an earlier post on this blog I wondered if American Gothic, in Moore’s Swamp Thing, was the first named storyline in mainstream comics. It wasn’t: The Judas Contract, a saga of child abuse and betrayal in The New Teen Titans, came the year before and had its own special logo on the cover and everything. So the story arc wasn’t an invention of Mature Readers comics. I look to Sandman, though, as the comic that popularised and standardised it; the named arcs, the logo on the covers, collection in trade paperbacks.

Nowadays it’s all arcs aimed at collection, the standard unit no longer the single issue but six issues. Together with price rises and widescreen storytelling it means that comics are extraordinarily bad value for money. You’ll get more story for your dollar almost anywhere but a comic. The initial thrill of these arcs, of knowing that this story had an end and wasn’t going to be forgotten, has been forgotten. Used well by good writers, they allow bad writers to abandon pacing for an eternal breathless present.

Sometimes I miss those older comics with no pretence of a beginning, middle or end. I miss that soap opera sprawl that let plotlines simmer for years or let writers launch into new ideas without concerning themselves with how they’d be resolved. Like Matt Murdock’s proposal to Heather Glenn, seemingly done on a whim by a young Frank Miller who surprised himself by resolving the plotline brutally and quickly. Or Chris Claremont letting the subplot of Storm’s lost powers roll on for 40 issues. They were messy, meandering comics but they had a certain charm.

Sometimes I miss those older comics with no pretence of a beginning, middle or end. I miss that soap opera sprawl that let plotlines simmer for years or let writers launch into new ideas without concerning themselves with how they’d be resolved. Like Matt Murdock’s proposal to Heather Glenn, seemingly done on a whim by a young Frank Miller who surprised himself by resolving the plotline brutally and quickly. Or Chris Claremont letting the subplot of Storm’s lost powers roll on for 40 issues. They were messy, meandering comics but they had a certain charm.

Hellblazer, for its first 40 issues, was a messy title. The opening splutter of one-offs turned into a story arc followed immediately by The Fear Machine, explicitly labelled as an arc but finishing a few issues earlier than planned. That led into the Family Man storyline which was interrupted by fill-ins and followed by fill-ins. Four issues drawn by Sean Phillips, which I’ll be treating as one body of work here, were spaced around a hallucinatory Delano one-off and a horror story by Alan Moore’s mate Dick Foreman. After these issues, three drawn by Steve Pugh mess around introducing a couple of new characters before moving Constantine through to Delano’s – and his character’s – conclusion.

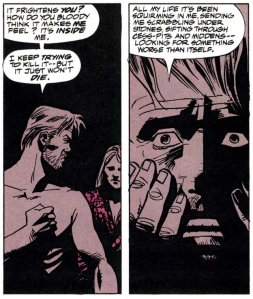

Delano has, by this point, abandoned plot. Those hoary horrors of the early issues, the demons and murderers and thugs, are gone. Hellblazer has become a psychological portrait, a camera circling John Constantine’s moral decay. Since the series began he’s betrayed a friend, sent a child to hell, cancelled the Second Coming, given a murderer his victims and killed a man. He’s seen his neighbours eviscerated and the community he joined torn apart. The closing chapters of Delano’s run are the study of a man coming apart, a man who chose to stand on the edge of the abyss and laugh who is only now understanding the price he’s paid.

The trilogy of Constantine in the present, past and future is preceded by an epilogue. #31’s Mourning of the Magician sees Sean Phillips replace the execrable Ron Tiner on art, but the transition from bad to good was eased by a mistake in colouring which made everything darker than it should’ve been. Phillips’s art uses a lot of black ink and flat panels anyway so whole pages can be hard to make out; in the original comic the blacks are actually lighter than some of the colours.

It’s a tale of the family Constantine: sister Cheryl, niece Gemma, and father Thomas. He’s dead before the story begins, of course, killed by the Family Man and so indirectly by his own son. But he isn’t gone. His ghost haunts his niece, silent and cold and confused. John turns up in time for the cremation, saying goodbye his own black-humoured way, and rolls his sleeves up for the exorcism. The good humour, the cynical dismissal of horror, that returned to him when he dispatched his father’s murderer is intact. What John’s forgotten is that the persistence of his dad’s spirit is his fault.

Comics are still, in 2012, a medium overawed by fathers. Superman has two fathers to remember and honour, as does Spider-Man. Batman’s veneration of his father is so exalted that he seems hardly to recall that his mother died at the same time. Every Hollywood hero has a father he can’t live up to. Even in horror, even in the medium that specialises in dark places, fathers are usually towers of strength and light. And here, in a comic 22 years old, is a hero who struck his father down and condemned him to a slow, lingering death. John Constantine cursed his father and, we discover, killed his mother. He only saved his father by the macabre touch of putting the rotting cat that his life-force was linked to into formaldehyde. We’ve travelled a long way from heroic.

Comics are still, in 2012, a medium overawed by fathers. Superman has two fathers to remember and honour, as does Spider-Man. Batman’s veneration of his father is so exalted that he seems hardly to recall that his mother died at the same time. Every Hollywood hero has a father he can’t live up to. Even in horror, even in the medium that specialises in dark places, fathers are usually towers of strength and light. And here, in a comic 22 years old, is a hero who struck his father down and condemned him to a slow, lingering death. John Constantine cursed his father and, we discover, killed his mother. He only saved his father by the macabre touch of putting the rotting cat that his life-force was linked to into formaldehyde. We’ve travelled a long way from heroic.

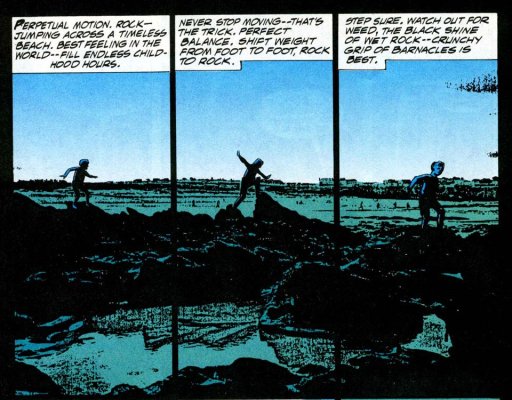

For all that it’s a redemptive tale. John faces up to the mistakes of his past and sets his father’s emaciated, one-armed, fire-blackened spirit free. But when he next turns up at the bus Marj and Mercury live in – an ex-lover and her wilful psychic daughter from the Fear Machine arc – he’s a drowning man. He’s been seeking the destruction he’s brought to others, rooting through the detritus of the Thatcher years looking for something that will penetrate the numbness, the invulnerable armour of the trickster. Being able to get away with anything can be exhausting. The daredevil yearns to be caught. Sickened by the toll his risk-taking has taken on others, sickened by his need for darkness he can triumph over, Constantine is a broken wreck. #34 is nothing but conversation, a late-night encounter, that poetic voice of Delano’s spilling over into the storytelling with an evocative page of a boy on a beach. Is it John? Is it just anyone, an unnamed child rockhopping toward us to make the metaphor real? Phillips’s thin black panel borders make the whole page a single composition, claustrophobic without white space but still spare in visual detail. It’s a technique he’d refine for Vertigo launch book Kid Eternity, dispensing with panels altogether. Here it makes an oppressive story of a filthy psyche both ugly and beautiful.

Dead-Boy’s Heart is a story of young Constantine navigating a world he doesn’t understand. He thinks it’s all about death: finding a child’s skeleton and a fossilised heart, playing pirates and red indians, crushing insects and in the end killing – perhaps – a bogeyman, a homeless derelict, a figure to torment and fear. But for the reader it’s all about sex: Cheryl getting rid of John to be with her boyfriend, the bigger boys sending him on a quest for porn, the couple fucking in the long grass he encounters on the way home, Auntie Dolly’s bondage sufferings, his father’s conviction for stealing knickers. John’s adrift in adulthood and finding it easier to comprehend pain than pleasure, confinement than freedom. He’s fighting adulthood, fighting understanding, fighting the sexual motive that overwhelms every adolescent. He doesn’t want to be beaten by something he doesn’t get. He knows his capacity for darkness is bigger than everyone else’s. So he fights sex with death and, in a way, wins.

Dead-Boy’s Heart – and note that hyphen, Dead-Boy is a character – is one of Delano’s masterpieces. Along with The Magus, the double-sized conclusion to the series, and the first annual about Kon-stan-tyn, the pagan repressor of feminine power, it’s one of the keys to Constantine’s enduring appeal. Someone’s done the work. Writers since may only have scratched the surface but the depths are there. Like Sherlock Holmes you can treat him as an adventurer if you like, pretend he’s just an action hero, but the psychology of his dysfunction remains the engine that drives him.

Dead-Boy’s Heart – and note that hyphen, Dead-Boy is a character – is one of Delano’s masterpieces. Along with The Magus, the double-sized conclusion to the series, and the first annual about Kon-stan-tyn, the pagan repressor of feminine power, it’s one of the keys to Constantine’s enduring appeal. Someone’s done the work. Writers since may only have scratched the surface but the depths are there. Like Sherlock Holmes you can treat him as an adventurer if you like, pretend he’s just an action hero, but the psychology of his dysfunction remains the engine that drives him.

After that there’s the future; a short hallucination induced by Mercury after some cat-and-mouse play about John’s intentions. Delano’s written a few dystopian futures and often has liberals and feminists in charge, which is curious given his espousal of female power. It’s a visually powerful sequence, an ancient but unrepentant John in a wheelchair pulled by dogs through a semi-submerged London, his faith in his own indestructibility fading but still there, like a curse of life. As he’s dragged below the water and into death he remembers it, remembers the taste from his youth and his life. It’s accepted and inevitable.

A planned trilogy, these three issues recall a Christmas Carol; ghosts of John in the present, the past and the future. But there’s no ending with a boy being asked if the turkey is still in the butcher’s window. Constantine is a Scrooge who knows his fate from the beginning, has seen his own grave and grinned at it. His dead friends haunt him every day. He knows full well the horrors of the present. All he needs to do, and what Delano needs him to do, is to clean out the accumulated grime and get his attitude back.

Hellblazer #31 is collected in the trade paperback Hellblazer: Family Man and Hellblazer #34 is collected in the trade paperback Hellblazer: Rare Cuts.